Back in May of 2023, I had never heard of “Pigeon Louse fly” (PLF), let alone seen one. At that time, I was busy documenting (taking pictures and videos of) the family life of a pair of wild Spotted neck doves as they went about raising their babies. As the photographing proceeded, I noticed a small, brown fly scuttling across the feathered body of a dove. It was the size of the common Housefly, 6-7mm long, yet looked different. It was flattened dorso-ventrally, with legs spread out on both sides. Its triangular head appeared sunken into the thorax, and its mouth parts pointed forwards, not downwards (see composite Image 1). I consulted Fly specialist, Dr Ang Yu Chen, from the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, of the National University of Singapore, who kindly identified it as the Pigeon Louse fly (PLF), Pseudolynchia canariensis.

Although it has a pair of lightly veined transparent wings, it seldom flies off the dove. It prefers to zip from point to point on the body of the dove, like the “Marvel” comic character, the “Flash.” It can move rapidly in any given directions, at a moment’s notice. This ability is helped by the presence of six strong legs, splayed out on both sides of its body, like a spider. The long muscular leg leads to a five segmented foot, ending in a bifurcated pair of claws. These claws provide for the flexible and firm grip on the smooth feathers of the dove. There are also numerous bristles/hairs on the legs, body, and head of the PLF. All these end in microscopic sensors for pressure, proprioception and direction; necessities for the success of the PLF’s movement (Image 2).

The whole fly is stream-lined to dive effortlessly in-between the feathers of the dove. The body and head of the fly is flattened. Thus, it is also commonly called the flat fly. The prognathous, triangular head is sunken into the thorax, with no visible neck. The pair of disproportionally large compound eyes occupies almost the entire lateral sides of the head. The large eyes most probably help it to see better in the dim environment of the space in-between feathers. The forward pointing mouth parts also allows it to immediately pierce the naked skin between the feather shafts. Blood is then sucked out of the pierced blood vessel to be emptied into the PLF’s stomach immediately. Hence, it obtained its food with one swift move. Pigeon Louse Fly (PLF) is a solenoid, hematophagous obligate parasite of pigeon/dove, meaning that if a PLF cannot find a pigeon host, it is unable to reproduce and will die out. Both male and female PLF feed exclusively on the blood of the pigeon. (? “Dracula” of the pigeon race). See image 3.

Taxonomy

Pigeon Louse fly belongs to the Family Hippoboscidae of the order Diptera (true flies with single pair wings). The Hippoboscidae family contains 213 species, and 21 genera. Examples of the Hippoboscidae family includes Pseudolynchia canariensis (Pigeon louse flies), Hippobosca equina (horse keds), Melophagus ovinus (sheep keds) and Lipoptena cervi (deer keds). Those species of Hippoboscids that parasitize birds are commonly known as ‘louse flies,’ while those that parasitize mammals, although like their avian counterparts, are known as ‘keds’. The members of Hippoboscidae family with three other families, Glossinidae (Tsetse flies), Nycteribiidae and Streblidae (both Bat flies) are all blood-feeding obligate parasites of their hosts.

Unique Life Cycle

The above four families are also previously known as pupiparous, meaning giving birth to live pupa. This is not completely correct. They give birth to the final, 3rd stage larva. This larva does not feed and is soon deposited (term used to describe the laying of the 3rd stage larva) after being formed within the female fly’s abdomen.

Unfortunately, there is little monetary grants given to research on the PLY. Hence, there are little definite data on the life cycle of the PLF. However, there are a lot of studies done on the economically and medically important Tsetse fly. I found two very good internet sources of the Tsetse fly to help illustrate the life-cycle of the PLF. See below (video 2)

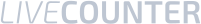

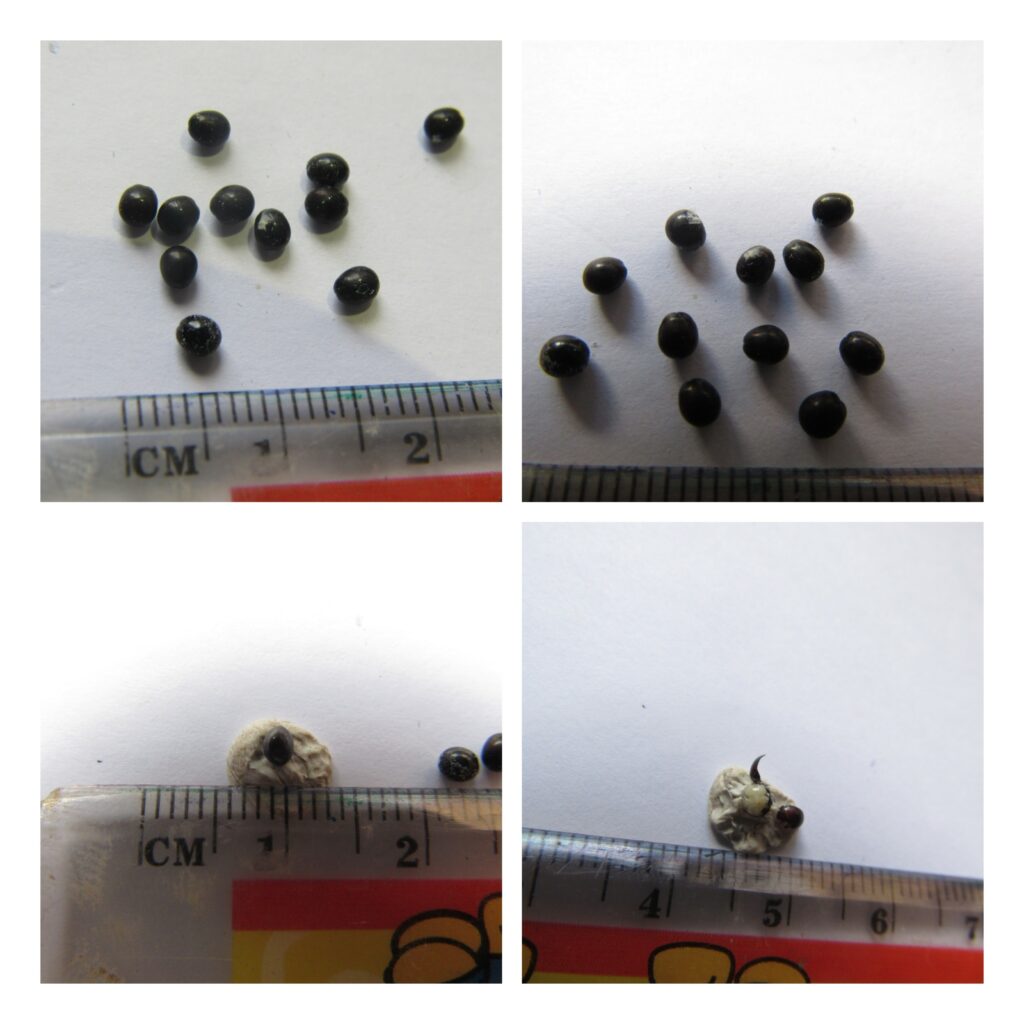

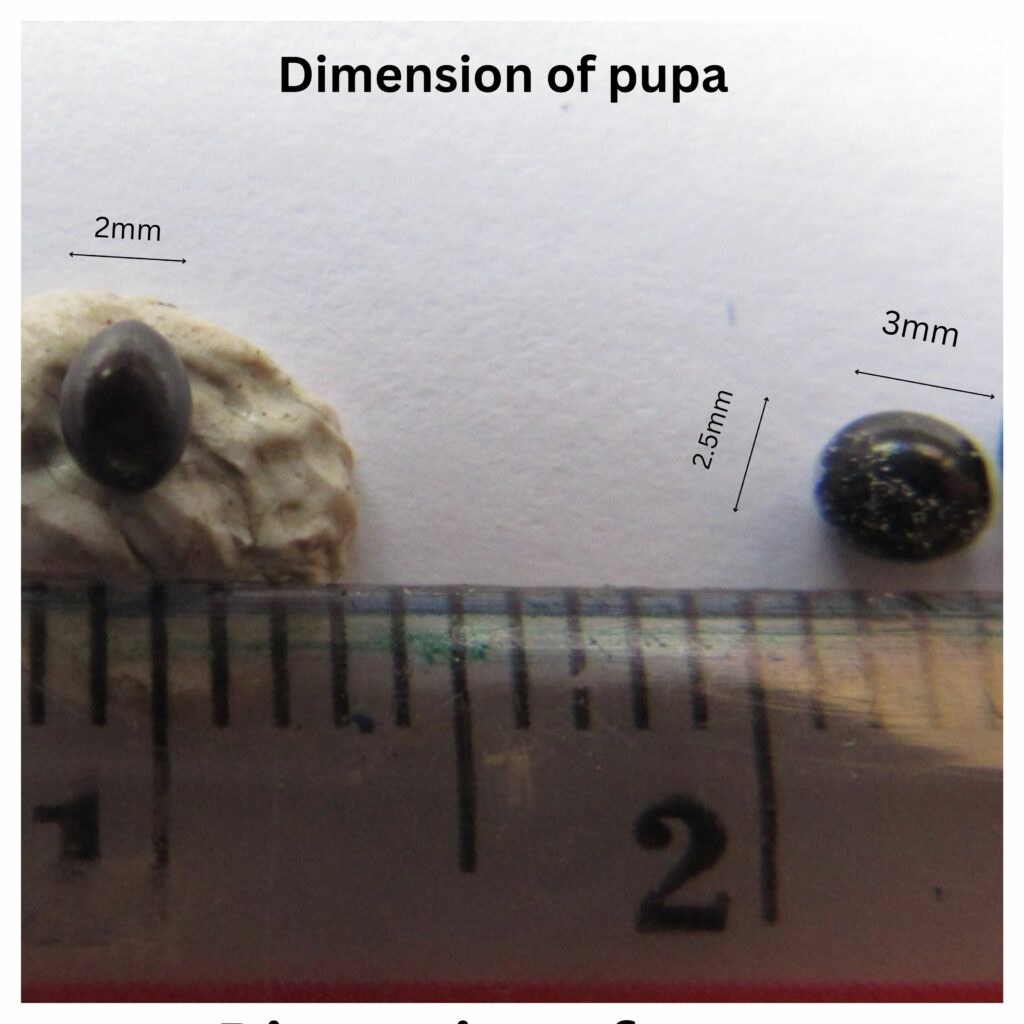

During the next 10 days after a female pigeon lousefly emerges from her pupa case, she matures, finds a host, takes her first blood meal, mates (usually only once in her lifetime) and produces an egg from her ovaries. The egg travels down the oviduct, is fertilised by sperms that has been stored in the spermatheca. The egg lands in the uterus and hatches into the 1st larva instar. Two specialised tubes in its head attaches to the milk glands on the uterus walls. The single larva feeds exclusively on its mother’s milk, grows and undergoes two moults. This milk, as with mammal milk, besides having carbohydrates and fats, is rich in 12 major proteins, as well as digestive enzymes and minerals that both feed the larva and help develop its immune system. The larva breathes through its abdominal polypneustic lobes, situated at its caudal end, and gets its oxygen supply directly from air passing in through the female’s vulva. After the 2nd moult, the 3rd stage larva occupies almost the whole of the female’s abdomen. It is deposited soon after, as a weakly motile fat, white oval shaped pre-pupa. The tail end which comes out first has a dimple and contains the respiratory apparatus. Within an hour, the white covering darkens to a black colour with loss of segmentation markings. The exuviae (cast off skin of a moult) of 3rd larva moult is not discarded but is incorporated into the hardened pupa shell. In tropical Singapore, it takes about 3 to 4 weeks for the adult fly to emerge from the pupa. From egg to depositing of viable pupa it most probably takes about 7 to 9 days. Adult female louse-fly most probably has a lifespan of 3 to 4 months. According to the Manual of the Neartic Diptera, hippoboscid females may produce just seven to eight offspring in a lifetime.

Under laboratory conditions, it has been documented: –

“Oct 1, 2008 · Female P. canariensis develop their first puparium six days after their first blood meal; one puparium is produced every two days (Arcoverde et al. 2009; Pirali)”

Further research is most probably needed to elucidate the life-cycle timings of the PLF under field conditions.

For comparison, below is a link to the beautifully illustrated life-cycle of the Tsetse fly:

http://www.raywilsonbirdphotography.co.uk/Galleries/Invertebrates/vectors/Tsetse_Fly.html

Ptilinum is an inflatable bag (like a car’s air bag) concealed within the front of the fly’s head. It is used to break the hard pupa case, along the pre-determined line of dehiscence when the fly is ready to emerge. The ptilinum is suddenly engorged with the fly’s blood, the endolymph. This causes the ptilinum to suddenly pop out from the front of the fly’s head. Unlike a car’s airbag, the ptilinum is filled with a liquid which is incompressible. Hence, the engorged ptilinum acts like a sudden hammer blow, causing the pupa case to split and release the new young fly. By deflating and inflating the ptilinum in succession the young fly is able to push away the dirt in front of it, creating a tunnel up to the surface of the ground. Once out of the ground, the membranous ptilinum is withdrawn completely into the front of the head, leaving only a visible inverted “U” scar.

Importance of Pigeon Louse Fly (PLF)

At the moment, the literature does not seem to attach much importance to the PLF.

PLF is currently known to be the vector and intermediate host for sporozoite production of the protozoan parasite of pigeons, Haemoproteus columbae. This results in the disease known as pigeon malaria. However, it is usually not fatal to the adult pigeon, and only fatal to young weak pigeons, maybe due to malnutrition.

Pigeon louse, in the suborder Ischnocera (clade Phthiraptera [Mallophaga]) is also found on the PLF. However, they are not parasites of the PLF, they merely make use of the PLF to transport them from one bird to another. This is known as a phoretic association between the louse and PLF..

PLF is parasitised by the mites, Myialges anchora (Myialgesidae).

References :-

- 1) Pseudolynchia canariensis – Wikipedia

- 2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odCtCote9U0

- 3) http://www.raywilsonbirdphotography.co.uk/Galleries/Invertebrates/vectors/Tsetse_Fly.html

- 4) https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/livestock/pigeon_fly.htm

- 5) https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/taxa/418801-Pseudolynchia-canariensis/browse_photos

- 6) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0020751908004062?via%3Dihub

- 7) https://wiki.nus.edu.sg/display/TAX/Pseudolynchia+canariensis+-+Pigeon+Fly

- 8) https://bugguide.net/node/view/1144369/bgimage

- 9) https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/app/uploads/2017/04/sbr2015-048.pdf

- 10) https://www.msdvetmanual.com/integumentary-system/flies/hippoboscid-or-louse-flies-of-birds

- 11) https://veteriankey.com/common-avian-diseases/

- 12) https://www.aavac.com.au/files/2009-11.pdf

- 13) https://ndvsu.org/images/StudyMaterials/Parasitology/Hippoboscidae.pdf

- 14) https://www.britannica.com/animal/tsetse-fly

- 15) https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/mve.12703

- 16) https://parasitipedia.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3135&Itemid=3571

- 17) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9779546/