I was in Victor Harbor on the 11th of August 2023, taking a leisurely walk along the Esplanade, feasting my eyes on the stunning seascape view of Encounter Bay, feeling the cool fresh breeze on my face, when suddenly I saw a bird hovering motionlessly in the near-sky in front of me. My first thought was a Nankeen Kestrel. I quickly broke out my camera and started taking pictures. It was a flurry of motionless activities. I had to keep my hands and body still in the strong breeze and kept the moving bird in the centre of the viewfinder and in focus over the backdrop of a featureless sky. It was only after all these were over and that I realised it was a totally different bird, a Black-shouldered kite, Elanus axillaris (BSK).

Over the next one month, I saw the bird 4 to 5 times in the open sky, near the mouths of the Inman and Hindmarsh Rivers.

Video of sequences of the BSK taken over a few days. Encounter Bay, Victor Harbor. August 2023.

Black-shouldered Kite (Elanus axillaris), also known as the Australian black-shouldered kite is a small raptor native to Australia, measuring around 35 cm (14 in) in length, with a wingspan of 80–100 cm (31–39 in). The female is larger.

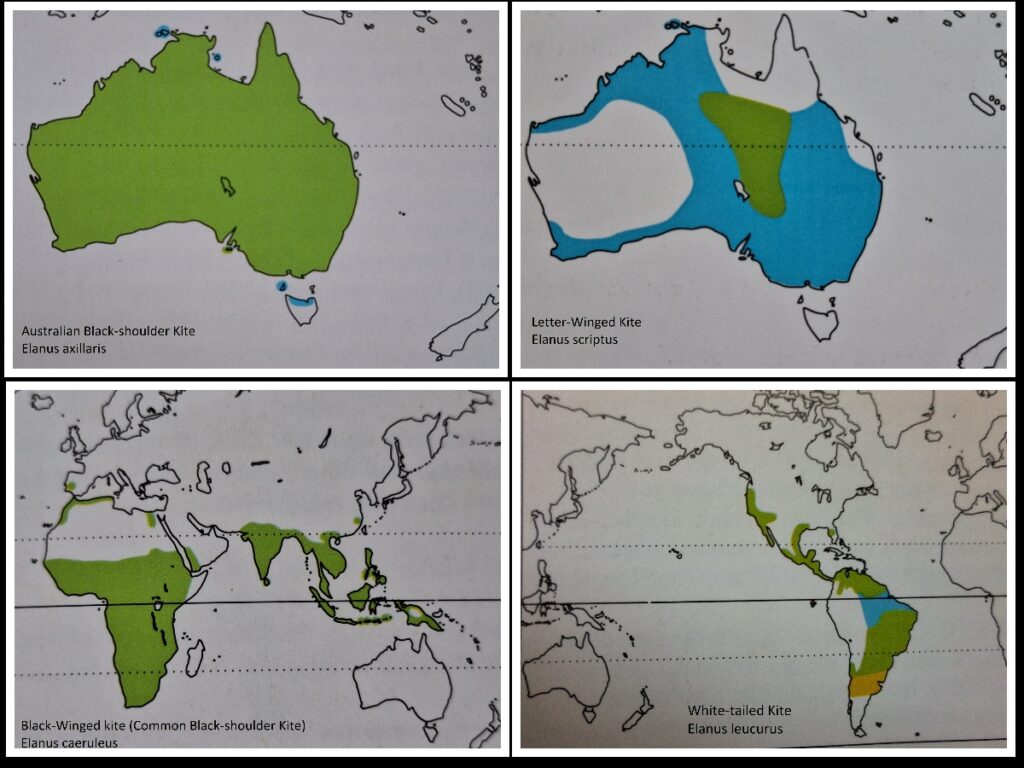

Elanus is a genus of the family Accipitridae (Hawks and Eagles). Elanus includes the following 4 species with a similar-looking appearances: –

Only two kites are found in Australia, but (1) the Letter-winged kite (Elanus scriptus) is a nocturnal hunter while (2) the Australian Black-shouldered kite (Elanus axillaris), a diurnal hunter.

Appearances

Black-shouldered kite (BSK) is generally a white bird with a black shoulder patch. The snowy white of its head continues into its neck and breast, down to its belly, vent, and tail feathers. On the dorsal side, the colour is generally light greyish, starting from the nape, down to the back, rump and central rectrices of the tail, while the rest of the tail feathers are white. Dorsally, the ashy grey outstretched wings are marked by black primary flight feathers and black lesser secondary covert feathers. These black coverts appear as the well-known “black shoulder” in the folded wings of a kite in an upright perch posture.

Ventrally, the white outstretched wing has a unique roundish black spot on the primary coverts near the black alula, in addition to the black-tipped primary flight feathers. This black spot is absent in the Common Black-shoulder kite (Elanus craeruleus), now better known as the Black-wing kite. The pure white tail lacks the dark band found on the other common hovering bird of prey, the Nankeen Kestrel, Falco cenchroides.

Its nostrils and the cere are yellow. Its legs and toes are also yellow, with long and sharp black claws. The short and stout black bill has a sharp, hooked tip to the upper mandible. This makes it a very efficient machine for ripping into and tearing up its prey.

Its forward-facing eyes are piercingly ruby-red. It has a bony shield over its eyes, like most hawks and eagle which gives it a fierce look. There is also a black comma-shaped mark, starting in front of the eye, stretching over the top of the eye, and trailing from the back of the eye towards the nape. This cosmetic mark also contributes to the fierce look.

Males and females look alike, except for females generally being slightly larger in size. Juveniles resemble adults but can be identified by the rusty brown wash on the head and upper chest, the mottled brown back and wings, white wing tips, and brown eyes.

Food

This small raptor has evolved into a specialised mouse-catcher. In one study, involving analysis of ejected pellets, 90% of its diet consist of the introduced House Mouse, (Mus musculus). It also eats other mouse-size mammals like rats, small birds, small reptiles like skinks, lizards, and large insects like grasshopper.

If one kite eats 3 mice a day, it would remove a thousand mice per year. In one observation, it was recorded that one kite caught 17 mice in one hour, ate some himself and brought the rest back to feed its hungry mate and nestlings. The farmers’ activity of planting crops and storing grains makes the House mouse, which he unwittingly brought along, very happy. The rodents multiply and their population explodes, cumulating in terrifying mouse plagues. However, Nature fights back, the kite is an evolved full-time mouse catcher. It is well known that kites congregate on a mouse plague, as much as 70 birds have been documented in one location. When foods are plentiful the kites may even raise a second brood in a year. Thus, in as short as 2-3 months the next generation of kites arises.

The Australian Black-shouldered kite (BSK) is rated as least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List of Threatened Species. Although reported throughout Australia, they are most common in the relatively fertile south-east and south-west corners of the mainland, and in south-east Queensland. This is to be expected as their food source is tied to the farms. Hence, in times of mouse plagues the farmers must be mindful about the use of pesticides, as this could kill the kites directly or indirectly, by causing thinning of the egg shells or malformations of the nestlings.

Hunting methods

Its favourite hunting method is by hovering motionlessly in the sky (80% of the hunting time). Other times it hunts from a high perch above ground. It heads into the oncoming winds with outstretched wings, slightly upraised in a “V” posture. To increase its buoyancy, it may fan its tail feathers and point them slightly towards the ground. It may flap its wings to gain height or to change to a new vantage point. While in the still posture, it intensely scans the ground 10 to 12 m (35 to 40 ft) below. Its large eyes, relative to the size of its head, are adapted to have sharp vision and the ability to detect any sudden, quick movements on the ground below. Once detected, it drops on its prey with a swift and silent glide, grasps its prey with extended, powerful claws, often killing it instantly. The silent downward snoop is reminiscent of the owl’s legendary silent flight. For mechanics of silent flight, please refer to the following websites (Ref. 14, 15, 16). One study documented a successful catch rate of 77%.

Breeding Behaviors

Breeding season takes place from August to December. During courtship, the mating pair will circle each other high in the air. The male may perform a “Butterfly-flutter” dance, a rapid fluttering of raised stiffened wings. It may then dive at the female, presenting her with a mouse. She would then flip, to fly upside down and grasp the offered food with her talons. They may then lock talons and tumble downward in a descending spiral, like a visual presentation of the statement “till death do us part.” Luckily, they part before hitting the ground. All courtship displays are accompanied by constant calling.

The next stage is nest building. The female is the only one who arranges the twigs into an untidy circular nest, approximately 28 to 38 cm (11 to 15 in) across, about 5 to 20 m (16 to 66 ft) or more above the ground, near the canopy top of an isolated or exposed tree in open country. When old nest is reused, (even of the Australian magpie or raven’s) the addition of new twigs can double the size of the nest to around 78 cm (31 in) across and 58 cm (23 in) deep. The male’s job is to supply its mate with twigs. Normally he is quite conscientious in his job, but should he be distracted from his work for too long a time, the female is not averse to fly off herself to get a twig or two herself.

The female lays about three to four dull white eggs specked with red-brown patches, of a tapered oval shape measuring 42 mm × 31 mm (1.7 in × 1.2 in). The eggs are laid at intervals of two to five days. She incubates them for about 34 days (5 weeks).

For Images of nest and eggs, please refer to following website :-

https://mdahlem.net/birds/6/blshkite.php

In one study, 3 nestlings were initially seen, but later only two were left. Subsequently the bigger chick was seen to grasp its brother by the neck. Luckily, the smaller brother managed to fight him off. Both survived to fledge. For the kites, it seems that the “Law of the Jungle” begins in the nest.

During the whole 5 weeks of egg incubation and the first 2-3 weeks of nestlings, the female does not hunt. She depends on her mate to bring her food. He usually brings the dead mouse to his favourite perch on a branch of a tree next to the nest tree. He then calls her. She would fly out from the nest and takes the mouse from him. She removes the mouse head and swallows it. She next opens the mouse abdomen and throws away the intestines. She would then eat up the mouse or bring it back to the nest to feed her babies. All these would take only 10 minutes. In the meantime, her mate would be standing guard, on top of the nest tree. He may even take a turn at the nest to keep the eggs warm. When the nestlings are young, she brings the headless carcass back to the nest, rips off small pieces to feed them. In their second week of life, the baby birds are given a whole decapitated mouse carcass to swallow down. By the third week, the babies are left alone in the nest. The mother bird joins in hunt to feed her babies. One of the parents is usually around to stand guard over the youngsters. The young birds usually fledge after 36 days, (5 weeks) as nestlings.

In the study, the male kite tries to mate with the female after the young birds fledge, but she rejected him and flew away, never to return. The male continues to look after the newly fledged kites for the next 5 weeks, protecting them, feeding them for at least the first 22 days, teaching them to hunt and to avoid dangers. They are capable of hunting after the first week. One year old kites are able to breed for the first time.

Thus, we can see that the kites have a clear division of labour, the female builds the nest (logical, since she must sit inside it for 8 weeks), the male supplies the twigs, she lays the eggs, broods them and look after the nestlings, the male supplies the food and looks after the young birds post-fledging, so that she could start brooding on the second set of eggs. Nature is so simple and logical.

Calls / Vocalizations / Sounds

For audio recordings, please see the following website: –

https://mdahlem.net/birds/6/blshkite.php

Generally silent, the Black-shouldered Kites’s vocalizations are mostly heard during the breeding season.

| Type of calls | Characteristic of calls |

| Primary call heard in flight or when hovering | clear whistled ‘chee, chee, chee’ |

| Perched | hoarse wheezing ‘skree-ah’ |

| Contact calls between pairs | short high whistles |

| Females / Older Juveniles | deep, soft, frog-like croak |

| Other Calls | harsh vocalizations when alarmed; harmonic, chatter, and whistle vocalizations in other contexts. |

References:

1) https://australian.museum/learn/animals/birds/black-shouldered-kite/

2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-shouldered_kite

3) https://ebird.org/species/auskit1

5) https://animalia.bio/black-shouldered-kite

6) https://peregrinefund.org/explore-raptors-species/kites/black-shouldered-kite

7) https://earthlife.net/black-shouldered-kites/

8) https://operationmigration.org/black-shouldered-kite-the-ultimate-guide/

9) https://www.sa-venues.com/wildlife/birds_black_shouldered_kite.php

10) https://birdssa.asn.au/birddirectory/black-shouldered-kite/

11) https://mdahlem.net/birds/6/blshkite.php

12) https://animals.fandom.com/wiki/Black-shouldered_Kite

13) https://www.une.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/29673/debus-et-al-bskite-afo.pdf

14) https://www.audubon.org/news/the-silent-flight-owls-explained

15) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7671161/

16) https://academic.oup.com/icb/article/60/5/1123/5840477?login=false

17) https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010518-040436

18) Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1 and 2

All photographs and video attribute Wong Kais.